Entries from March 1, 2017 - March 31, 2017

Chinese money trends suggesting economic stability

Chinese monetary strength has moderated in recent months but current trends continue to give a positive message for economic prospects.

The PBoC yesterday released additional monetary data for February, allowing calculation of the preferred narrow and broad measures here – “true” M1 (which adds household demand / temporary deposits to the official M1 aggregate) and M2 excluding financial sector deposits (which are volatile and contain little information about near-term economic prospects).

Six-month growth of real (i.e. consumer price index-deflated) true M1 fell sharply between October and January but stabilised in February and remains at a solid level by historical standards – see first chart. Earlier narrow money buoyancy was only partially reflected in GDP growth, tempering concern about the recent pull-back. Real true M1 growth, moreover, bottomed in late 2014 more than a year before the trough in GDP growth, so any economic slowdown may not occur until late 2017.

Real non-financial M2 growth strengthened less dramatically in 2015-16 and has arguably been a better guide to economic performance. A pick-up last summer / autumn suggests that GDP momentum will rise near term while a more recent slowdown has been modest and is of limited concern – first chart.

January / February activity data this week, meanwhile, suggest stable economic momentum. Six-month industrial output growth remains within its recent narrow range – second chart. Private investment continues to recover, rising by an annual 6.6% in January / February, with enterprise money trends still giving a positive signal – third chart. Worries about a sharp slowdown in housing momentum were allayed by data showing sales and starts growing by 23.7% and 14.8% annually – fourth chart.

Posts in late 2016 (e.g. here) suggested that solid economic growth and rising inflation concerns would prompt monetary policy tightening in early 2017, contributing to a slowdown in capital outflows. The PBoC today announced further 10 basis point increases in repo and MLF (medium-term lending facility) rates. Foreign exchange reserves, adjusted for valuation effects, rose in February for the first time since June, with the offshore / onshore forward yuan spread signalling the possibility of a further increase this month – fifth chart.

UK Q4 GDP strength fading in Q1

UK data on industrial / construction output and services turnover released today suggest a further upward revision to fourth-quarter GDP growth but a significant slowdown in the current quarter.

The last GDP release on 22 February reported growth of 0.7%, or 0.71% before rounding, between the third and fourth quarters of 2016. This estimate incorporated quarterly increases in industrial and construction output of 0.3% and 0.2% respectively. These numbers were revised up to 0.4% and 1.0% in today’s releases, implying a rise in GDP growth to 0.76%, assuming no other changes. Services output seems unlikely to be revised down, since services turnover – which feeds into the output data – also grew by slightly more than previously estimated in the fourth quarter. The revised GDP release on 31 March, therefore, may report quarterly growth of 0.8%.

January data, however, suggest that current-quarter growth will be significantly lower. Industrial and construction output both fell by 0.4% between December and January, while services activity also seems to have weakened slightly, based on the turnover data. GDP is estimated here to have eased back by 0.2% in January to stand 0.3% above the fourth-quarter level. Assuming a resumption of moderate growth in February / March, this suggests a first-quarter GDP increase of 0.4-0.5%. Note that another batch of monthly data will appear before the Office for National Statistics releases its preliminary first-quarter estimate on 28 April.

Is the US jobless rate bottoming?

The US unemployment rate fell to 4.7% in February but remains above a low of 4.6% reached in November 2016. The judgement here is that it may stabilise or edge higher, for three reasons.

First, the jobless rate is inversely correlated with the job openings or vacancies rate, which has retreated from a peak in April 2016 – see first chart. Companies are reluctant to lay off workers – reflected in a low level of weekly initial unemployment claims – but the decline in the openings rate suggests that they are not stepping up recruitment. This may partly reflect uncertainty about healthcare and tax reforms.

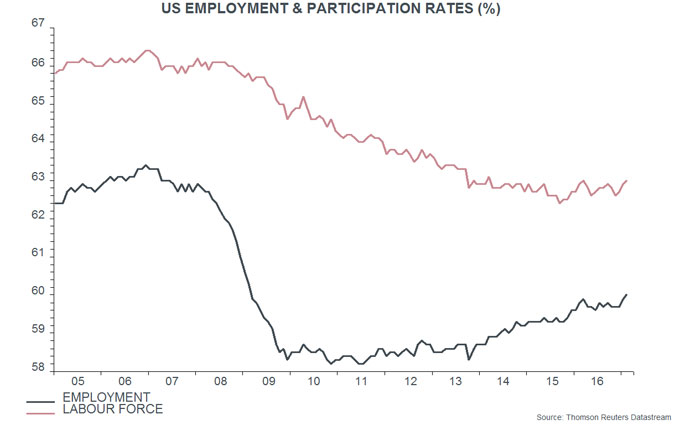

Secondly, the labour force participation rate – the percentage of the civilian population in or seeking work – has stopped falling. It may even be embarking on a modest upward trend – second chart. The combination of population growth and a rising participation rate may allow moderate employment expansion to be maintained without a further reduction in unemployment.

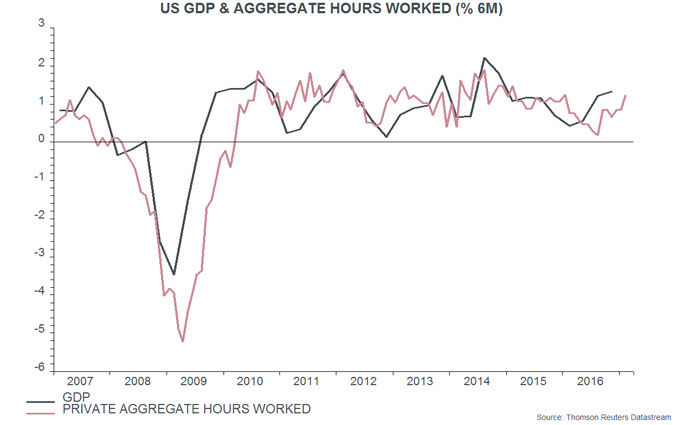

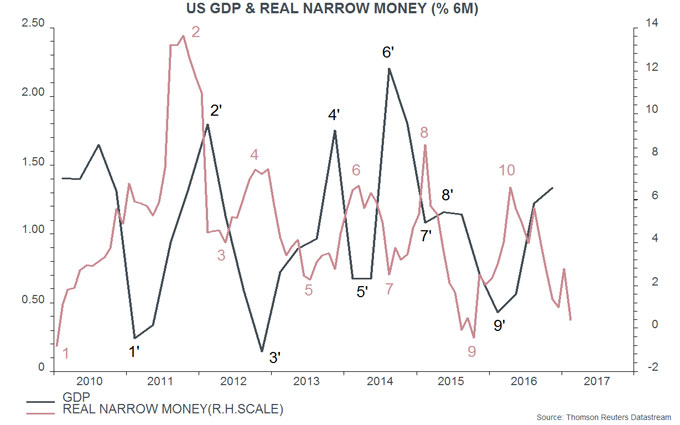

Thirdly, growth of labour demand is coincident with or lags GDP expansion – third chart. As previously discussed, real narrow money trends suggest a GDP slowdown into the summer – fourth chart. Recent elevated unit labour cost growth adds to the risk that companies will curb recruitment if economic expansion moderates.

Global leading indicator supporting monetary slowdown signal

The OECD’s leading indicators are giving tentative confirmation of the forecast here, based on real narrow money trends, that global economic momentum will peak in spring 2017 and slow into the autumn.

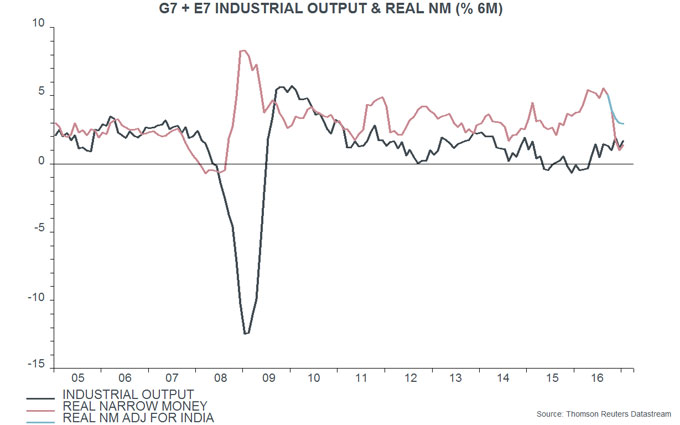

The OECD this week released January data for its country leading indicators. Note that the January estimates of the trends in the components incorporate February data where available – so the indicators already reflect strong February business survey results, for example. The country information is combined and transformed here to create a global (i.e. G7 plus E7) leading indicator of industrial output. Six-month growth of this indicator continued to rise in January but the one-month increase fell back – see first chart.

As previously discussed, global six-month real narrow money growth peaked in August 2016, suggesting a peak in industrial output expansion around May 2017, allowing for an average nine-month lead. Six-month growth of the leading indicator may have peaked in January, based on the fall in one-month momentum. It typically leads by four to five months, so this would suggest a peak in economic momentum in May-June, consistent with the monetary signal.

The prospect of a summer economic slowdown, coupled with the Fed’s recent hawkish shift, may imply stronger headwinds for equity markets and other risk assets. Any setback, however, could prove to be modest and temporary if investors believe that the economy will retain reasonable momentum and / or reaccelerate in late 2017.

Such a scenario cannot be ruled out based on current monetary data. Global six-month real narrow money growth, while well down from last summer, remains at a respectable level by historical standards, after adjusting for an excessively negative signal from Indian M1 due to the demonetisation programme – second chart. The recent fall has partly reflected a sharp rise in six-month consumer price inflation, which is likely to moderate if commodity prices stabilise at their current level. In the US, February narrow money numbers may have been depressed by a delayed send-out of income tax refunds, reflecting legal changes: refunds last month were $25 billion lower than in February 2016, equivalent to 0.9% of the narrow money stock measure tracked here – third chart.

UK Budget: safety-first now, autumn fireworks possible

Chancellor Hammond was constrained by Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts showing little carry-over of this year’s borrowing undershoot into future years. With no “back of the sofa” money to spend, Mr Hammond opted to raise taxes to plug the funding gap for social care and pay for additional business rates relief and higher spending on education / training. He did so by hiking national insurance contributions for the self-employed and – unexpectedly – slashing the recently-introduced dividend allowance.

The net effect of all government decisions – including the boost to spending from the recent cut in the personal injury discount rate – is to raise borrowing by £3.1 billion in 2017-18, with the amount falling in the subsequent two years and turning into a reduction of £1.0 billion in 2020-21. These numbers are rounding errors – £3.1 billion is equivalent to 0.15% of forecast nominal GDP in 2017-18.

Mr Hammond’s caution may partly reflect a desire to delay major initiatives until the new Autumn Budget. He may have greater room for manoeuvre by then, since borrowing may continue to undershoot the OBR’s forecast. A key assumption is that nominal GDP growth will fall from an estimated 4.2% in 2016-17 to 3.3% in 2017-18, contributing to a slower increase in tax receipts. However, nominal GDP rose by an annual 4.9% in the fourth quarter of 2016 and monetary trends suggest continued solid expansion in 2017 – see chart.

The new OBR numbers show an odd-looking profile for cyclically-adjusted net borrowing, which now rises from 2.6% of GDP in 2016-17 to 2.9% of GDP in 2017-18 before dropping sharply to 1.9% in 2018-19. The suggestion is that fiscal policy will be expansionary this year but will turn significantly contractionary next year, when the Brexit uncertainty drag on growth may reach a peak. This profile looks implausible: solid nominal GDP growth may result in stronger tax receipts and lower borrowing in 2017-18, while the Chancellor may choose to deliver a significant fiscal stimulus this autumn to cushion the Brexit effect.

US ISM consistent with spring global growth peak

The US Institute for Supply Management (ISM) manufacturing new orders index – widely followed as an indicator of US / global industrial activity – reached its equal highest level since 2009 in February. This is consistent with the suggestion from global narrow money trends that economic momentum will rise to a peak in spring 2017 before slowing into the second half of the year. The ISM orders index is expected here to fall back over coming months.

Narrow money trends provide a significantly longer lead on future economic activity than the ISM survey. The first chart shows the ISM new orders index and six-month global real narrow money growth pushed forward six months. The strong February ISM reading matches a peak in real money growth in August 2016. Based on this relationship, the ISM orders index may have reached a peak in February and is likely to decline into mid-year.

Three other considerations suggest that ISM strength will fade. First, the February orders surge partly reflected increased inventory building, which is likely to prove temporary. The ISM inventories index rose to its highest level since 2015 last month.

Secondly, consumer spending on goods has slowed, suggesting insufficient final demand to maintain the current pace of orders expansion. Three-month growth of retail sales volume fell to 0.6%, or 2.5% annualised, in January – second chart – while February auto sales were lacklustre. Demand for capital goods is recovering but probably not enough to offset this softness.

Thirdly, ISM strength has not been confirmed by East Asian business surveys, which usually act as a bellwether of global trends. The Federation of Korean Industries February survey, indeed, reported a marked weakening of business expectations, although this may be partly attributable to political and corporate scandals – third chart.

The pattern of recent years has been that periodic slowdowns in the global economy have swiftly led to additional monetary policy stimulus, limiting and eventually reversing any damage to equities and other risk assets. Major central banks, however, may take a tougher line this year, reflecting low unemployment rates, high headline and rising core inflation, and a growing “populist” backlash against low / negative rates and neverending QE.