Entries from July 1, 2012 - July 31, 2012

Odds shortening on UK Bank rate cut

The Monetary Policy Committee is likely to stand pat at next week’s meeting but the “MPC-ometer” model used here to forecast decisions remains firmly in the easing zone, suggesting further action – probably in the form of a cut in Bank rate – over coming months.

The MPC-ometer predicts the monthly policy decision based on the latest values of 12 economic and financial inputs, including business / consumer confidence measures, GDP growth, inflation, wage increases, measures of price expectations, credit spreads and the stock market. Since its introduction in 2006, the model’s forecasting record has compared favourably with the consensus prediction of the monthly Reuters interest rate poll, with periodic “misses” generally due to it moving before the MPC – the model, for example, signalled that “QE3” was likely as early as May.

The model’s output is in the form of the forecast average interest rate vote* of MPC members, with readings of above +12.5 or below -12.5 basis points suggesting a rise or cut respectively in Bank rate. Since Bank rate reached an effective lower bound in early 2009 – at least as judged by the MPC until recently – undershoots of the -12.5 threshold have signalled expansions of QE. The historical performance of the model (estimated on the full data set) is shown in the chart – movements out of the shaded “neutral” zone are usually associated with Bank rate changes or QE announcements.

The last data point in the chart is an August estimate based on data for two-thirds of the inputs and assumptions that 1) tomorrow’s second-quarter GDP estimate shows a fall of about 0.5% (i.e. consistent with a flat economy adjusting for the Diamond Jubilee bank holiday) and 2) components from business and consumer surveys released around month-end are unchanged. The result is another reading below the -12.5 threshold, suggesting further policy easing.

Such action is unlikely next week. The MPC will not wish to amend the announced QE3 programme so soon and will also need time to assess the stimulative impact, if any, of the “funding for lending” scheme (FLS) – the model forecast does not take account of this additional initiative (though will if it translates into improvements in the components, e.g. narrower credit spreads or a recovery in business confidence). The suggestion, however, is that the MPC will be prepared to move again in September if economic and financial indicators remain at current levels.

The most likely next step is a cut in Bank rate to 0.25%. The MPC was previously concerned that this would damage credit supply by squeezing banks’ net interest margins but the cheap funding offered through the FLS is now expected to have an offsetting impact. The possibility of a Bank rate reduction has also been opened up by the ECB’s decision to lower its deposit rate to zero (and official musings about the imposition of a negative rate); this has contributed to recent upward pressure on sterling versus the euro. The MPC, in theory, could lower the rate paid on reserves without cutting Bank rate – thereby protecting banks’ interest income from tracker mortgages – but this looks too complicated and would further weaken linkages between the official rate and market rates.

*For example, if five members want to raise official rates by 25 basis points while four prefer no change, the weighted-average vote is +14 (five-ninths of 25).

Is US velocity plunging?

Current US economic weakness was predicted by a fall in real money supply expansion in late 2011 / early 2012 – see previous post. Real money growth has stabilised recently at a respectable historical level but pessimists argue that this will not prevent a recession because of a decline in the velocity of circulation.

Velocity can be thought of as the flow of GDP income generated by each dollar of the money supply. The pessimists cite the ratio of current nominal GDP to the current M2 money supply in support of their claim; this ratio has plunged since early 2011, reaching its lowest level since 1950 – see chart.

There are, however, two problems with the pessimists’ argument. First, the money supply affects nominal GDP with a lag – of about six months for activity and two years for prices, according to the Friedmanite rule. Velocity, therefore, should be measured by comparing current nominal GDP with the money supply between two and eight quarters earlier. As the chart shows, the ratio calculated using a five-quarter lag – a reasonable compromise – is still above its 2010 low, though may fall as a bulge in M2 in mid 2011 enters the calculation (unless nominal GDP accelerates).

Secondly, velocity should be measured with reference to a broad monetary aggregate that is unaffected by voluntary shifts between different types of account. The M2 surge in mid 2011 was caused by an inflow from large time deposits and institutional money market funds – components of the old M3 definition. The velocity of a broader “M2+” measure incorporating these “wholesale” forms of money – and calculated using a five-quarter lag – has recovered significantly from a 2010 low and may continue to trend higher (since M2+ has been growing much more slowly than M2).

The view here remains that the probability of a US recession in 2012 is higher than in 2010 and 2011 but still well below 50%, based on recent continued expansion of real narrow money.

Global real money uptick hints at late 2012 economic improvement

Global economic news is expected here to remain weak during the third quarter, reflecting the lagged impact of a sharp slowdown in real narrow money into the spring – see previous post. Six-month real money expansion in the G7 plus emerging E7 economies, however, stabilised in April / May and appears to have recovered modestly in June, based on early data – see first chart. If confirmed, this recovery holds out hope of a revival in economic momentum in late 2012, allowing for the typical six-month lead.

Caution is still warranted. The final June reading will depend importantly on Eurozone monetary data released next week. The suggested recovery in real money expansion, moreover, mainly reflects a fall in inflation in response to commodity price weakness, which is now reversing – second chart. A sustained pick-up, in other words, will require faster nominal monetary growth – plausible in light of recent policy easing but not guaranteed.

The third chart shows six-month real narrow money expansion for the countries in the global aggregate that have reported for June. The US slowdown paused last month while Brazil’s recovery continued. Policy easing there has been much more aggressive than in China, where narrow money remains weak, suggesting that hoped-for economic reacceleration is unlikely before late 2012 at the earliest.

UK equities: will institutional selling slow?

Direct holdings of UK shares accounted for just 7.7% of the total financial assets of UK insurance companies and pension funds (ICPFs) at the end of the first quarter of 2012, down from a peak of 46.6% in the first quarter of 1998, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Aside from 7.3% at the end of last year, this represents the lowest weighting on record in official data extending back to 1964.

The 39.0 percentage points withdrawn from UK equities over the past fourteen years has been reallocated to bonds (+15.9), mutual funds (+11.2), derivatives (+4.9), long-term loans (+4.4) and foreign equities (+1.8) – see first chart.

A small part of the reduction is attributable to institutions preferring to hold UK equity exposure indirectly via mutual funds. ICPFs’ indirect holdings of quoted UK equities accounted for 62% of their direct exposure at the end of 2010, according to the annual ONS share ownership report. Applying this proportion to the 7.7% of directly-held UK shares at the end of the first quarter suggests total exposure of 12.4% (i.e. 7.7 times 1.62) – still far beneath the historical average for direct holdings.

“Structural” sales of domestic shares by ICPFs may have acted as a drag on UK relative equity market performance in recent years. The weighting will probably fall further but the low absolute level suggests that the pace of selling will, at least, slow. Institutions' cash ratio, meanwhile, is about average by past standards – second chart.

Euro weakness / cost containment boosting peripheral competitiveness

The external labour cost competitiveness of peripheral Eurozone economies continued to improve in the first quarter of 2012, although the gap with Germany remains large.

The charts show real effective exchange rates (REERs) based on unit labour costs, as calculated by the ECB. These measure costs in each country relative to a trade-weighted basket of its competitors within and outside the Eurozone*, expressed in a common currency. The indices are rebased to 100 in the first quarter of 1999, when EMU started.

Pressure for peripheral cost adjustment ratcheted up in mid 2010 after the first Greek crisis / bail-out. In the 18 months from the third quarter of 2010 to the first quarter of 2012, REERs fell by 7.1% in Spain, 5.4% in Greece, 4.6% in Ireland, 2.8% in Portugal, 1.3% in Italy, 0.6% in France and 0.5% in Germany. (All countries benefited from a fall in the euro over the period.)

Spain’s REER is now below its EMU starting level, in contrast to rises in France and the Netherlands.

Peripheral countries, of course, may have locked into EMU with overvalued exchange rates, implying that further downward adjustment will be required to lay the foundation for export-led growth. The REERs, however, dispel the notion that they have suffered a major loss of competitivess relative to core countries – with the obvious exception of Germany.

*The external grouping comprises the 10 non-euro EU member states, Australia, Canada, China, Hong Kong, Japan, Norway, Singapore, South Korea, Switzerland and the United States.

UK headline inflation fall improving economic prospects; "core" still sticky

The surprise fall in CPI inflation from 2.8% in May to 2.4% in June mainly reflects weaker food and fuel prices along with an early start to the summer sales. The latter effect should unwind in July while “good news” on food and energy prices may be nearing an end, with commodity markets rebounding strongly over the past month – the S&P / Goldman Sachs all-commodities index is up by 9.1% in sterling terms.

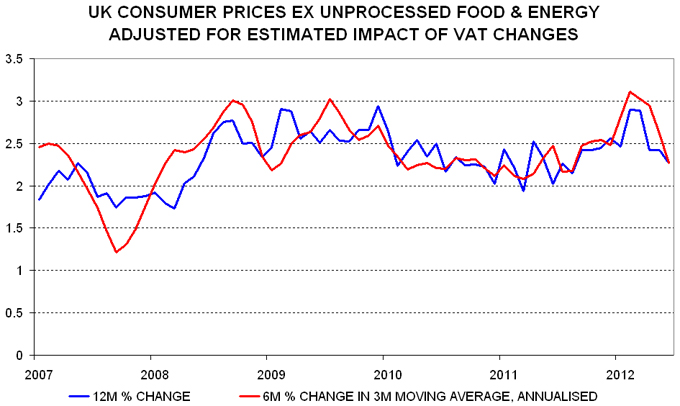

The annual change in “core” prices, as measured by the CPI excluding unprocessed food and energy, fell from 2.4% to 2.3%, with the decline attributable to the summer sales effect. Smoothed and seasonally adjusted, this index rose at a 2.3% annualised pace in the six months to June – see chart. Core pressures, in other words, remain inconsistent with the 2% inflation target, despite recent economic weakness.

The lower headline rate is improving economic prospects by contributing to a pick-up in real money supply expansion. Real non-financial M4 rose by 2.6% annualised in the six months to May, the fastest since April 2009, suggesting a return to respectable growth during the second half – see previous post.