Entries from August 20, 2023 - August 26, 2023

Why have real yields risen?

Why have global government bond yields picked up over the summer despite weakening PMIs and neutral / favourable inflation news?

The rise is attributed here to a further deterioration in the global “excess” money backdrop driven partly by unexpected output strength as an easing of supply constraints has allowed firms to work off order backlogs. Output is expected to realign with weak / falling incoming demand during H2, suggesting a reversal of liquidity tightening.

The rise in nominal yields has been driven by the real component with inflation expectations little changed.

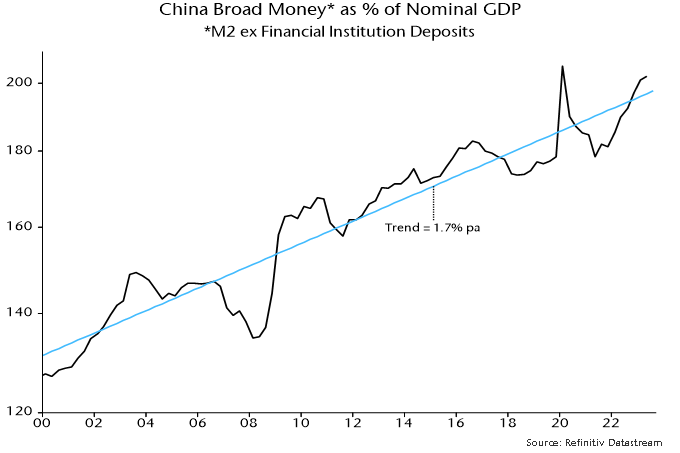

Changes in real yields have been inversely correlated historically with changes in global “excess” money momentum, as measured by the differential between six-month rates of change of real narrow money and industrial output – see chart 1.

Chart 1

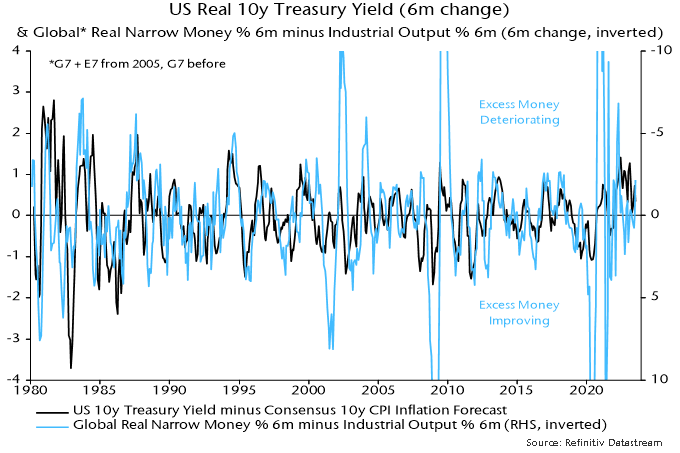

This differential has been negative since early 2022 but was expected to narrow as monetary tightening fed through to weaker economic activity and slowing inflation lifted real money momentum. Instead, industrial output growth rose to a seven-month high in June while nominal money weakness has offset a disinflation boost to real momentum – see chart 2.

Chart 2

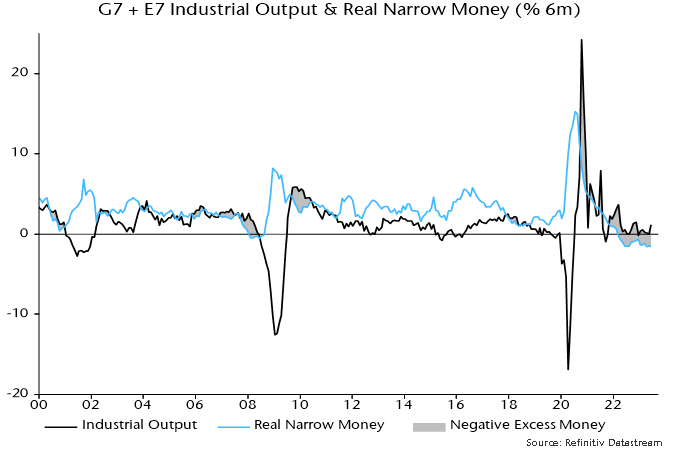

Production resilience was signalled by a recovery in the global manufacturing PMI output index, which crossed 50 in February on the way to a May high. It moved back below breakeven in June / July, however, with August flash results suggesting a return to the December 2022 level or lower – see chart 3.

Chart 3

Covid-related supply disruption resulted in the PMI output index lagging the new orders index in 2021 / H1 2022, but the position has reversed over the past year as production bottlenecks have eased, allowing firms to fulfil outstanding orders.

With the PMI delivery speed index – an inverse indicator of bottlenecks – hitting a 14-year high in May, the supply catch-up is probably ending, suggesting that the PMI output index – and hard production data – will converge with weaker new orders. At the current level of the latter index, this would imply output contraction.

The real narrow money / industrial output momentum differential, therefore, is likely to narrow unless nominal money data weaken further and / or consumer price inflation rebounds (unlikely). While G7 tightening is still feeding through, stable / easier monetary policies are expected to promote money growth recoveries in EM.

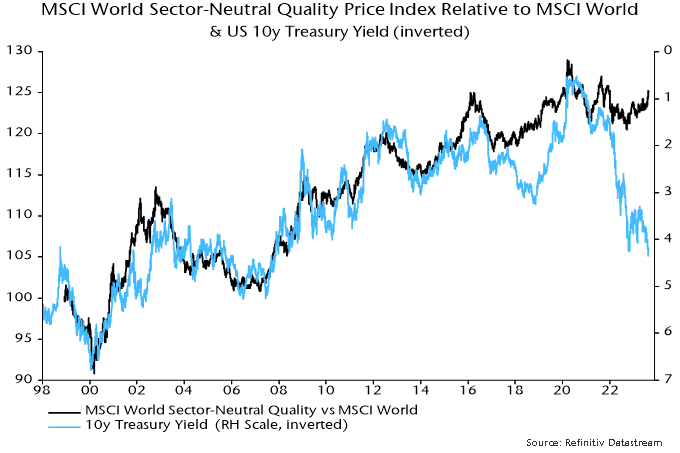

Commentaries here have suggested that the monetary / economic backdrop would favour quality stocks in 2023. The MSCI World quality index is 7.1% ahead of MSCI World in price terms year-to-date (as of yesterday’s close). This mainly reflects a high weighting in tech, but the sector-neutral quality index (which imposes MSCI World sector weights) is also now outperforming the main index and has reversed its relative weakness in 2022 – see chart 4.

Chart 4

The recent relative gain is striking against the backdrop of rising Treasury yields, with which the style has been inversely correlated historically, as the chart shows. The divergence is reminiscent of 2018, when the quality relative embarked on a sustained rise in February but a fall in Treasury yields was delayed until November. This year’s quality rally also started in February, suggesting a resolution of the current disconnect with yields by year-end.

Chinese weakness due to policy misstep

Pessimistic commentators argue that the Chinese economy has entered a “liquidity trap” and faces Japan-style deflation. This assessment is not shared here: a recent monetary slowdown can be explained by misguided policy tightening around end-2022, which is now being reversed, while broad money growth would need to fall much further to suggest a sustained decline in prices.

A review of monetary policy in recent years is helpful in understanding current conditions. An important consideration is that – like the Fed decades ago – the PBoC does not announce changes in its policy stance, which often become apparent only after the event in movements in money market rates and credit / monetary trends.

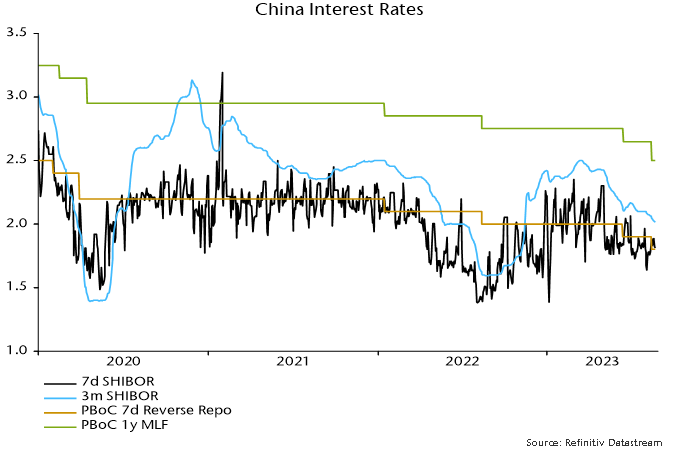

The PBoC eased policy between late 2020 and summer 2022 to cushion covid-related economic weakness. Three-month SHIBOR fell from over 3% to 1.5%, while six-month growth rates of money and credit began to pick up from mid-2021 – see charts 1 and 2.

Chart 1

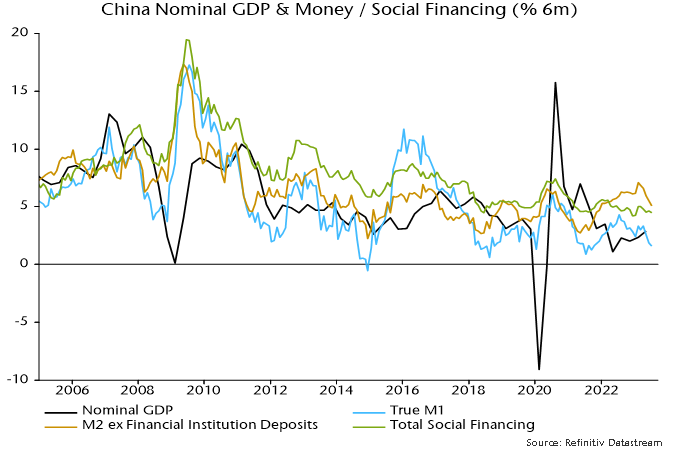

Chart 2

Narrow and broad money measures continued to accelerate in H1 2022, laying the foundations for a solid post-reopening economic recovery in H1 2023 – real GDP grew by 6.1% annualised between Q4 2022 and Q2 2023.

The PBoC, however, blotted its copy book in late 2022, tightening policy on misplaced concern about a reopening-driven inflation pick-up, although narrow money and credit growth were by then cooling and the ratio of broad money to nominal GDP was close to trend (in contrast to the US / Europe, where a large monetary overhang fuelled strong price pressures).

Three-month SHIBOR rebounded from 1.7% in September to 2.4% by year-end, rising further to 2.5% in March. The consensus view at the time – not shared here – was that the rise in money rates reflected stronger money demand due to reopening, i.e. the increase was “endogenous” rather than policy-driven and would not threaten economic prospects.

Policy tightening has resulted in six-month narrow and broad money growth falling to late 2021 levels, although credit expansion has declined by less (despite a very weak July flow number) – chart 2. The monetary slowdown suggests a loss of economic momentum through late 2023.

The PBoC has, at least, been swift to recognise its error, resuming easing in early Q2. Three-month SHIBOR has retraced half of its August-March rise but may need to return to the low to offset recent monetary damage.

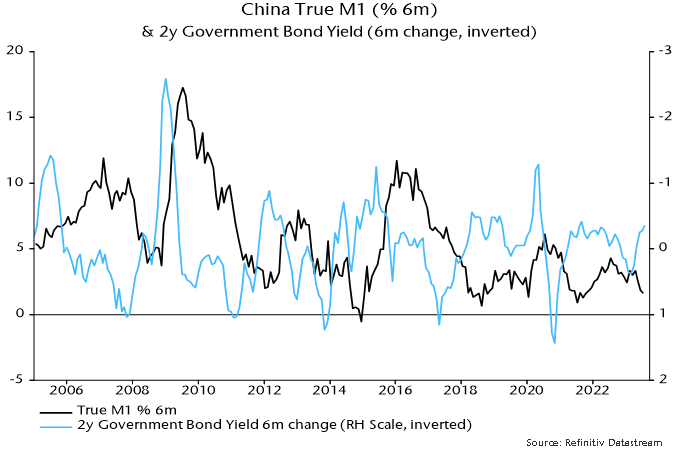

Chart 3 illustrates the inverse leading relationship between changes in interest rates (in this case the two-year government yield) and narrow money momentum. The reversal in rates suggests a bottoming out and revival in money momentum, although timing is uncertain.

Chart 3

Why did Japan enter a sustained deflation in the early 1990 and are there parallels with current Chinese conditions?

From a monetary perspective, a deflationary environment requires (broad) money growth to fall below the sum of trend real GDP growth and the trend rise in the money / nominal GDP ratio.

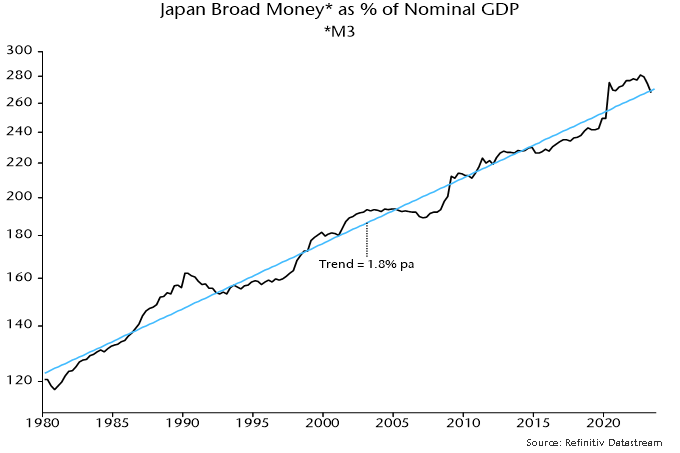

The ratio of Japanese broad money M3 to nominal GDP has risen by 1.8% pa on average over the long run – chart 4. Trend real GDP growth was running at about 2% in the early 1990s, so broad money needed to expand by about 4% pa to maintain stable prices. Annual growth fell below this level in 1991 on the way to zero in 1992, averaging 2.7% over 1991-2000.

Chart 4

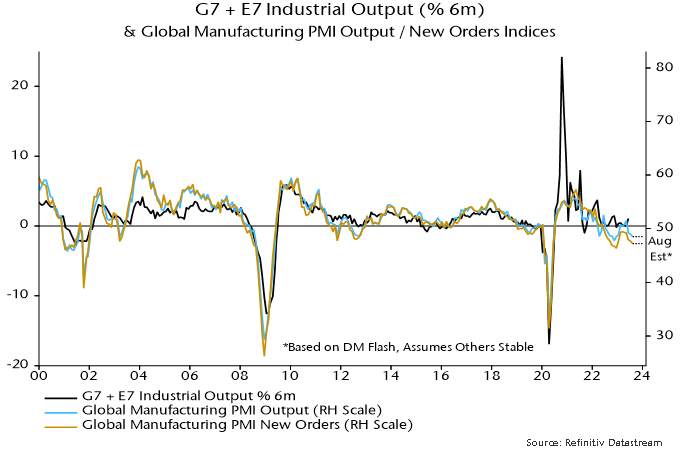

China’s broad money to nominal GDP ratio has risen at a similar trend rate of 1.7% pa – chart 5. If trend real GDP growth is assumed to be about 5%, broad money expansion needs to stay above about 7% to avoid a deflationary scenario. Annual growth is currently 11.6%, with the six-month rate of increase at 10.4% pa.

Chart 5