Entries from May 1, 2022 - May 7, 2022

UK recession now odds-on

Six-month growth rates of UK narrow and broad money – as measured by non-financial M1 / M4 – fell in March. With six-month consumer price momentum rising further, real rates of change moved deeper into negative territory – see chart 1.

Chart 1

The six-month contraction in real narrow money in March was slightly larger in the Eurozone than the UK – chart 2 – but UK weakness will intensify in April as CPI momentum is boosted further by the rise in the energy price cap . Eurozone six-month CPI momentum, by contrast, eased slightly last month, according to flash data.

Chart 2

Expressed at an annualised rate, UK six-month broad money growth was 4.2% in March, close to a 4.5% average over 2015-19 and a pace that, if sustained, would ensure medium-term compliance with the 2% inflation target.

A six-month contraction in real narrow money of the present scale was historically a reliable indicator of future economic weakness but did not always signal a recession.

A recession probability model was previously developed here combining monetary information with a range of other financial variables. Based on end-March data, the model estimates the probability of a recession in 2022 at 70% - chart 3.

Chart 3

The probability estimate is derived from an equation for the annual change in gross value added (GVA) including the following variables: real narrow money, real broad money, real broad money held by private non-financial corporations, short- and long-term interest rates, short- and long-term credit spreads, real share prices (FTSE local UK), real house prices and the effective exchange rate. Adjustments were made for the impact of strikes and the 1974 three-day week. The equation was estimated on data up to end-2019 to avoid the covid shock / recession.

The model "explains" the annual GVA change three quarters ahead using current and lagged values of the inputs. The recession probability estimate refers to the likelihood, based on the model, of a negative annual GVA change three quarters ahead, i.e. the 70% estimate refers to Q4 2022. (A negative annual change is a stricter requirement than the conventional recession definition of successive quarterly falls in GDP / GVA.)

Monetary relief for bonds?

Global six-month real narrow money growth fell to zero in March*, the weakest since the GFC and a level historically consistent with recession – see chart 1. (The current reading matches a low before the 2001 recession.)

Chart 1

A rebound in six-month industrial output growth, meanwhile, extended in March, reflecting a production catch-up from weakness in H2 2021 due to supply-side constraints. The negative real money / output growth gap, therefore, widened further.

The March fall in real money growth was driven by a further spike higher in six-month consumer price momentum. Nominal money growth was little changed – chart 2.

Chart 2

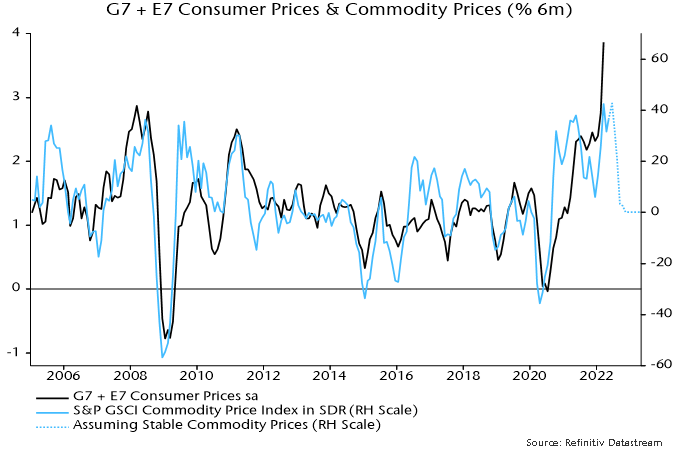

The historical relationship with commodity prices suggests that CPI momentum has overshot and will pull back, possibly sharply – chart 3.

Chart 3

Six-month industrial output momentum, meanwhile, may move back into contraction because of Chinese covid disruption and weakening trends elsewhere, reflected in soft April global manufacturing PMI results – chart 4.

Chart 4

Nominal money growth will probably weaken in response to rising rates and as central banks end / reverse QE but falls in CPI and industrial output momentum may dominate, resulting in a narrowing of the negative real money / output growth gap. The gap, indeed, could return to positive territory by mid-year – sooner than previously expected here.

This gap is a proxy measure of global “excess” money, which – on the monetarist view – is a key driver of demand for financial and real assets**.

Historically (i.e. from 1970-2021), global equities underperformed US dollar cash by 6.7% pa on average when the gap was negative, outperforming by 12.2% pa when it was positive. These numbers refer to month-ahead returns based on the most recent reading of the gap.

Equities underperformed cash on average when the gap was negative whether or not it was widening or narrowing. The average loss, indeed, was larger when the gap was narrowing. So the near-term message for equities remains unfavourable.

It is, however, a different story for bonds. Historically, Treasury returns have been sensitive not to the level of the gap but rather its rate of change. That is, a positive change in the gap has been associated, on average, with a fall in Treasury yields (and a negative change with a rise) – chart 5.

Chart 5

This year’s yield surge is “explained” by the move in the gap into deep negative territory.

Historically, the average fall in yields associated with a positive change in the gap was similar for positive and negative levels of the gap.

The prospective change of direction of the gap, therefore, suggests that the bond bear market is ending.

A reversal in yields would have implications for equity sectors / styles. Quality historically outperformed when excess money was negative but suffered this year from its correlation with yields – the magnitude of the yield rise may have weakened its usual defensive character. (Overweight consensus positioning may also have contributed to underperformance, i.e. quality had become momentum). A yield decline could allow a performance catch-up.

The MSCI World sector-neutral quality index has already reversed more than half of its earlier YTD underperformance despite further bond market weakness, with this recovery another indication that a yield top may be imminent – chart 6.

Chart 6

*G7 plus E7 aggregate. March estimate based on monetary data for all countries except Canada, Brazil and Korea (extrapolated).

**An additional proxy measure monitored here is the deviation of 12-month real narrow money growth from a long-term moving average. Historically, global equities outperformed cash on average only when both measures were positive. This second measure is expected to remain negative until late 2022, at least.