Entries from March 11, 2012 - March 17, 2012

Are the economy and markets approaching a peak?

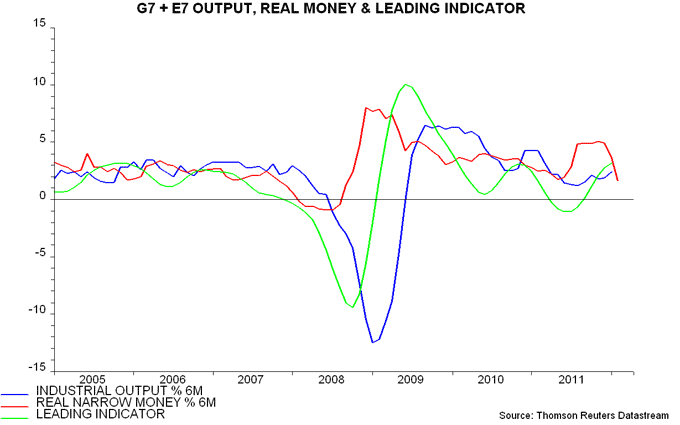

Six-month growth in G7 plus emerging E7 real narrow money topped out in November 2011 and available information suggests a further sharp fall in February – see first chart. Allowing for the typical six month lag between real money and economic activity, this is consistent with industrial output expansion peaking in May and slowing into the second half.

The forecast of a further pick-up in output momentum into May is supported by a shorter-term leading indicator derived from the OECD’s country leading indices. This indicator typically leads by three months and continued to rise in January, based on data released on Monday – first chart. If the monetary signal is correct, the indicator may peak in February, implying a March fall to be reported in mid May.

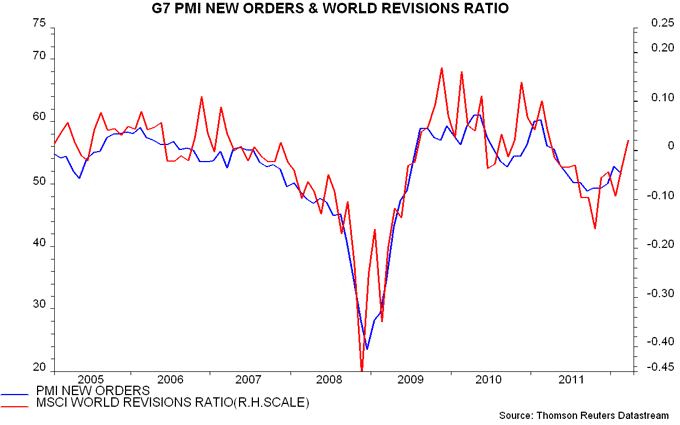

A further indication that near-term economic news may remain firm is that equity analysts are, on balance, revising up their company earnings forecasts. This, in turn, suggests that March manufacturing PMI results will be upbeat – second chart.

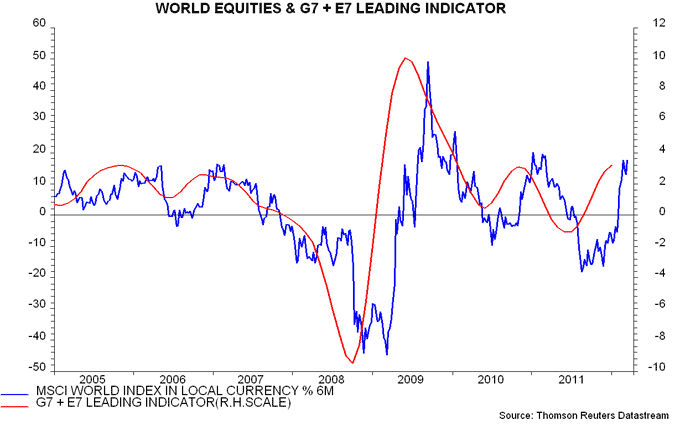

Growth peaks are usually associated with at least temporary declines in equities and other risk assets. Should investors cut risk exposure now in anticipation of an economic slowdown after May? Some reduction is probably warranted but it may be too early to position defensively, for three reasons.

First, equity market tops have tended to coincide with or even lag growth peaks in recent years. A “safe” strategy has been to wait for the leading indicator to fall before cutting exposure, even allowing for the two-month publication lag – third chart. On this view, the earliest date to turn defensive is mid April in the event of a February indicator decline. As noted above, however, the monetary forecast favours March as the first month for a fall.

Secondly, equities, historically, have tended to rise as long as annual growth of global real narrow money exceeds that of industrial output, implying “excess” liquidity – this is still the case now. Six-month rates of expansion, however, have crossed, based on the provisional February real money number – first chart. This could presage a “sell” signal from the annual comparison in mid 2012.

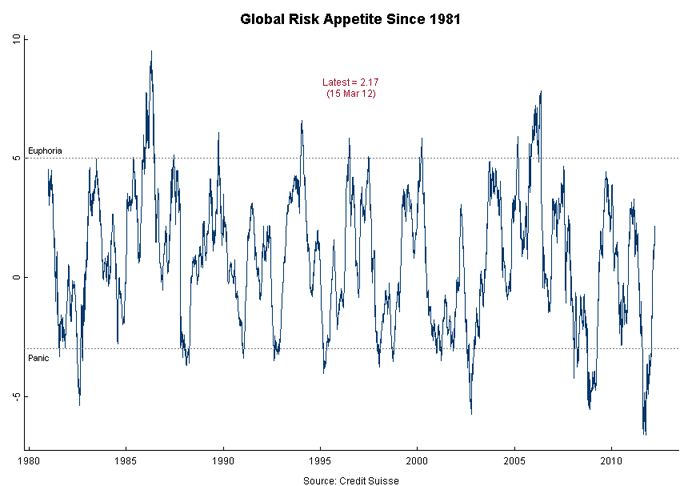

Thirdly, investor sentiment, while recovering dramatically since late 2011, has not yet reached an overbought extreme characteristic of major equity market tops, at least judging from the normally-reliable Credit Suisse risk appetite measure – fourth chart.

An additional argument for adopting a neutral posture is uncertainty over the monetary impact of the ECB’s liquidity injections – a pick-up in Eurozone real money growth could, in theory, temper or reverse the recent global slowdown. February money supply figures are released on 28 March and will be an important influence on the assessment here (though will not incorporate the impact of the second three-year LTRO conducted late last month).

"Osborne bond" talk obscures falling effective maturity of UK debt

The 100-year “Osborne bond” is intended to “lock in” low long-term borrowing costs by extending the average maturity of the public debt. Any such impact, however, will be small relative to the reduction in the effective maturity of official liabilities stemming from the Bank of England’s QE programme.

According to the Debt Management Office (DMO), the average maturity of gilts and Treasury bills outstanding was 14.5 years at the end of 2011. This figure, however, includes about £275 billion of gilts held by the Bank of England, representing 21% of the stock of debt held outside the DMO.

The market has, in effect, exchanged these gilts for zero-maturity central bank reserves. The relevant metric for assessing refinancing risk is the average maturity of the market's combined holdings of debt and reserves, not that of the stock of debt including the Bank's gilts. This “effective” maturity is estimated to be 11.5 years currently, down from 13.7 years at the end of 2008, just before QE started – see chart. (The calculation assumes, reasonably, that the average maturity of the Bank’s holdings matches the outstanding stock of debt.)

The effective maturity will fall further to an estimated 10.7 years when the Bank completes its £325 billion QE programme, assuming no other changes.

The Bank of England pays Bank rate on reserves. This results in an interest saving when Bank rate is below the initial yield on purchased gilts, as at present. The Bank, however, could be forced to tighten monetary policy aggressively in the event of a funding or inflation crisis. This would be instantly reflected in the combined government / Bank interest bill.

The UK's "true" debt maturity is still significantly longer than for other major countries but QE has eroded the advantage and will swamp the impact of any “Osborne bond”.